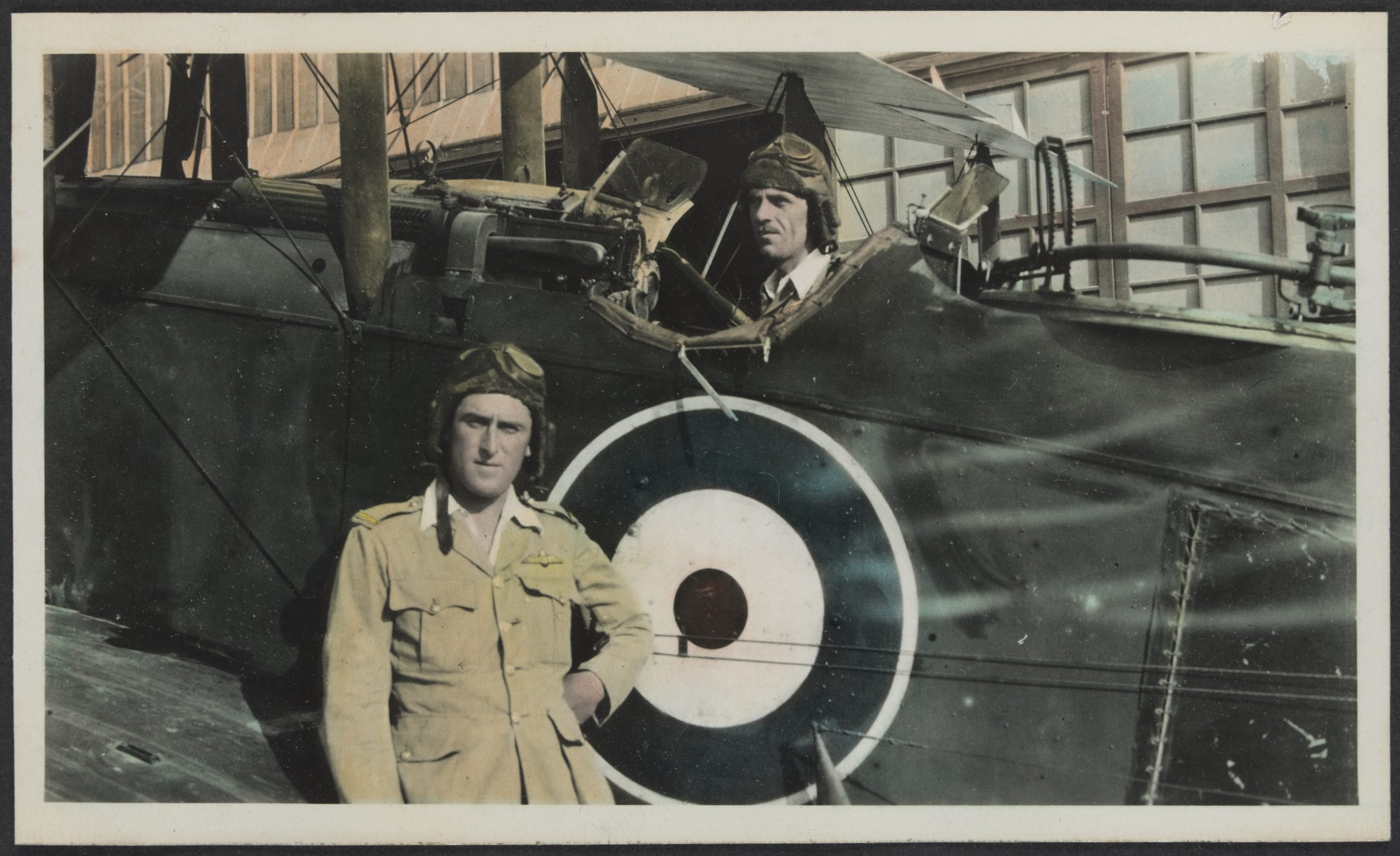

Charles Pratt in Cockpit WW! 1917

1.

The Birth of Surveillance

Up up we went until houses became mere replicas of those made from toy blocks by children. Evergreen trees looked ridiculously uniform in shape, resembling the miniature pines associated with the days of our youth and Santa Claus’s toy gifts. Picking out familiar houses and points resolved itself in a fascinating puzzle, which grew by bounds as we sailed along. The Geelong Football ground was presented by an oval the size of a bracelet, whilst the Eastern Cemetery looked exactly like a piece of “pepper and salt” tweed. (Geelong Advertiser, 1920)

This describes one of the first joy rides Charles Pratt flew from Geelong’s Belmont Common where he set up his aviation business, “Geelong Air Service Pratt Bros” after the First World War in 1920. The complete lyrical description from which this quote was taken invokes images of colour in me, a sensation not generally invoked by the high contrast black and white photographs that mark the period. These ‘new frontier’ joyrides upped the ante on the Amusements of St. Kilda’s Luna Park introduced 8 years earlier, for example. Whereas Luna Park cost 6 pence to enter, a sky flight was significantly higher. In his often-mundane diary, which he fastidiously kept all his life Charles Pratt noted; “I took up five in the morning and five in the afternoon altogether collected £7.” (Pratt, Jan 1. 1920)

Charles Daniel Pratt (1892-1968) started working life as a New Zealand grocer in Helensville coming to Geelong after the First World War. He had enlisted in the army from 1914-18 and served in the Gallipoli campaign, where he was wounded, as well as the Egypt and Palestine campaigns, serving in the New Zealand Engineers, in the motor dispatch riders, receiving a Victory Medal, with his final service in the Royal Flying Corps based at Ismailia with the No. 113 Squadron RAF. He rose from private to Lieutenant during his service and was a proficient flyer when war ended. The Palestine campaign marked the beginning of photographic air reconnaissance to discern military movement and to clearly map difficult terrain. The new aerial photographic tool extended British military surveillance and mapping of the region. The First World War trained many pilots in air photography with improved technologies requiring both a pilot and photographer. Aerial photography had come of age in the Palestine campaign by augmenting inadequate maps of the Turkish Front. Such reconnaissance morphed into an essential post-war cartographic instrument, an efficient contemporary technique for marking and visually containing Empire. This technical advance predicted the later digital use of Google maps to contain the world at an even more pervasive and insidious level.

At war’s end these early planes that Pratt had learned to fly became war surplus. With the family inheritance of the father who had recently passed away Pratt bought two De Havilland GH6s, an Avro 504 and a Sopwith Pup, disassembled and crated for shipment from the Suez Canal to Wellington New Zealand. Geelong was chosen for residency by chance. Charles had bought the shipment of 4 crated planes and found difficulty in moving to Wellington from the docks in Melbourne due to an industrial dispute on the wharves. As a result he assembled one De Havilland plane there with help of engineers from the transport ship at No 10 Berth. Central Pier, Victoria Dock. Pratt taxied the assembled De Havilland, skimming over crates, precariously missing an overhead crane and the masts of nearby ships to park at a Port Melbourne airfield. He subsequently flew around Port Phillip Bay, discovering the Belmont Commons as a good place to offer joyrides around the area, leasing it in 1920 with residence established at 200 Latrobe Terrace, Geelong.

Pratt’s migration and settlement transformed a war machine on which he had heroically performed into a joyride experience for his passengers. His Aerial photography marked and historically documented the emerging suburban and industrial landscapes of Geelong and Port Phillip Bay. The speed of movement around Victoria and landscape vistas was unique, but a 100 years later such views became available on every digital device globally. The mechanics of surveillance has migrated out of the landscape and directly in the bodies of all those citizens sitting frozen and staring at a computer screen. Pratts’ engagement with technology straddles that gap.

Geelong Waterfront 1923

2.

Theatre of Surveillance

Photographs are a way of imprisoning reality, understood as recalcitrant, inaccessible; of making it stand still. (Sontag :165: 1977)

Surveillance and photography have a long historical relationship. The evolution of the mechanics of the recorded image runs parallel with the rise of modern surveillance society. During photographic exposure, light reflected off the subject falls through the lens and induces changes in the photosensitive film, or more recently onto digitalised pixels. This physical and fundamental connection between the subject and the material of the captured image, the ‘indexicality’ is intrinsically linked to notions of truth. It is here the surveilled image indicates a direct, rather than arbitrary, connection between a sign and its referent. This unique relationship creates potential for the medium to produce artefacts that testify through their physical presence, rather than pictorial representation, to the exposure having taken place.

When, considered only as images, despite their apparently immediate, natural and non-mediated relation to what they represent, photographs function as culturally coded signs that operate in a sphere of meanings that are entirely human. The problem with this mode of analysis is it privileges the theory or audience who builds the system of meaning, rather than the practitioners as creative producers of or active participants in knowledge creation.

The photographic ‘object’ is often designed and considered to fix the visible with results that are usually interpreted in terms of meaningful visual signs exclusively from the perspective of a disembodied spectator. David Abram notes this exclusion of ecological positioning is located in modern Western tendencies to abandon dynamic interactions between human and non-human in favour of technologies. The result is not only a distancing of self from other, but also a significant loss of an embodied perception. Abram notes:

Transfixed by our technologies, we short-circuit the sensorial reciprocity between our breathing bodies and the bodily terrain. Human awareness folds in upon itself, and the senses – once the crucial site of our engagement with the wild and animate earth – become mere adjuncts of an isolate and abstract mind bent on overcoming an organic reality that now seems disturbingly aloof and arbitrary. (Abram 1997: 267)

Can the disembodiment and the mechanization of the mechanized and disembodies surveillance gaze be challenged by a revisioning or re-looking at surveillance images? Emphasising the physical and material value of the image highlights a move beyond the mere representational passive, static gaze and engagement with subject. That it, it is possible through photographic processes to produce an embodied entity that actively participates in the surrounding world and go beyond the constraints of the apparatus yielding predictable visual results. Photographs can be open to chance occurrences that manifest, for example in the digitalising of Pratt’s glass sides we are able to see the random pattern of markings, scratches and bleaching resulting from post-processing handling. Re-visiting Pratt’s images in combinations with new technologies incites new investigations with reconfiguring of past knowledge and stimulates new ways of knowing (and making) that includes a deeper understanding and engagement with phenomena of the moment of capture and considerations of looking.

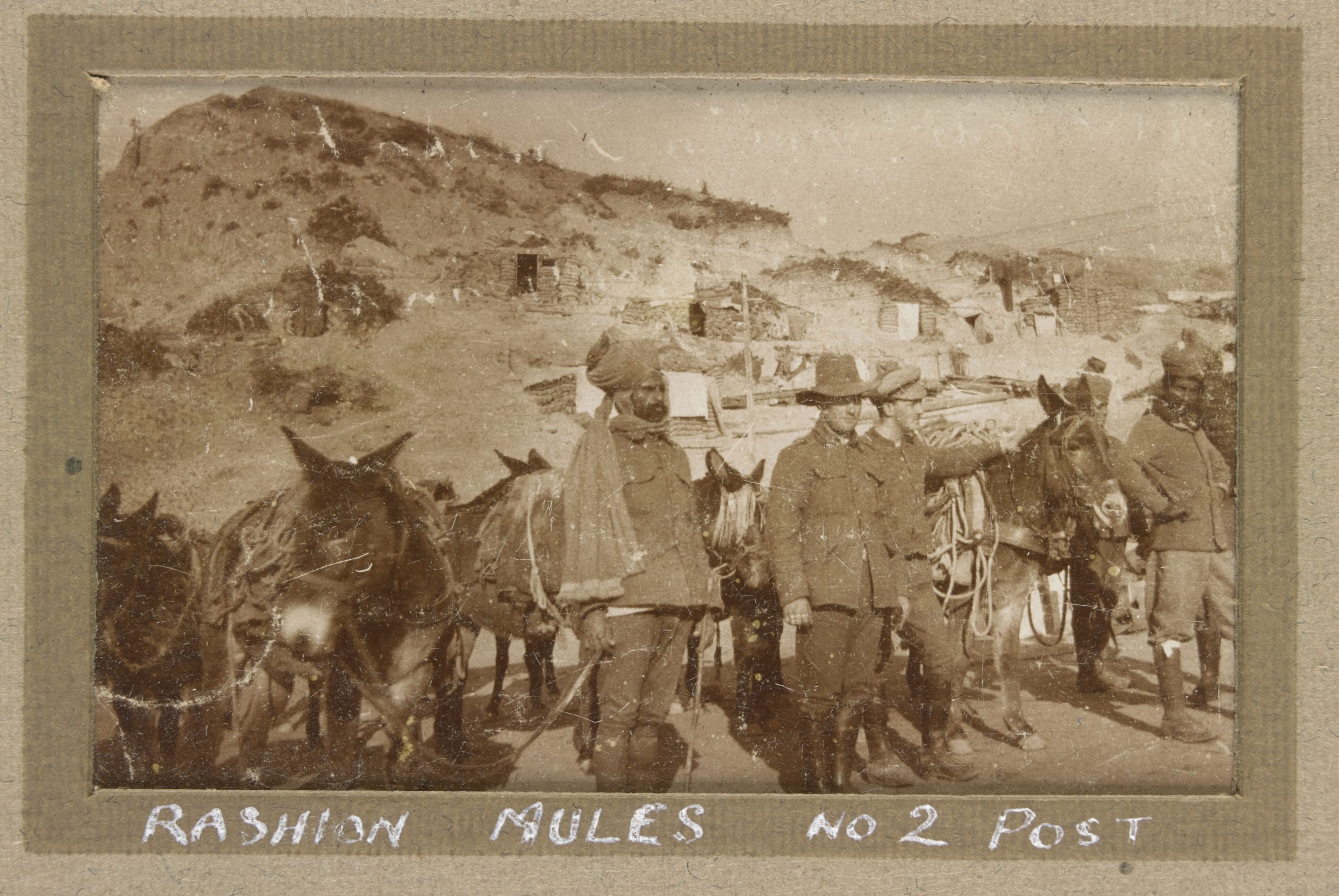

ANZAC Mules WWI (Charles Pratt)

3.

ANZAC

On his return to Egypt, one of these life changing opportunities came in the form of a request from the Royal Flying Corps for volunteers to learn to fly. Early in the war it was thought that it would be essential for fliers to come from the better educated classes, however it was found that better education has little to do with motor skills and that good horsemen and cycle riders had these. (Reilly, p.3 2016)

Pratt’s upward mobility into the air was not only a physical one but also signified a rise in class. He migrated through technology from a physical presence in the heat of battle into an emerging form of mobile surveillance that, at this initiating phase, required body centred knowledge and acumen. The prestige gap between what was considered the second-rate education system of the Mechanics Institutes and the Technical School for trades and crafts (Preston, 2005) compared to the Secondary School system and the elitism of the tertiary training available to the monied and privileged classes is breached by the necessities of war. Interestingly, on his settlement in Geelong Pratt re-connected locally with his photographic craft through the Photographic Club at what was then Gordon College.

It is productive to explore how a trace of such a class system re-asserts itself in emergent contemporary contested technological fields. A gap between technology and the body is extended, for example, in contemporary war machines. Satellite images of the Ukraine/Russian border documented the amassing of troops and at the other polar end of this gap all men between 18 and 60 are conscripted to physically defend Ukraine. Missiles launched from the safety of Russian Screens hundreds of miles away are more effective than Russia’s bogged down on the ground conscripted troops. Pilotless drones search a contemporary sky embedded with foreboding and fear.

On the ground before his aerial call Pratt’s photographs documented ships of ANZAC soldiers in transit to Gallipoli from Mudros Bay, Lemnos. He photographed the tents on Waterfall Gully on Bauchop’s Hill, on the Gallipoli Peninsula. This location was taken by the New Zealand Mounted Rifles on 6 August 1915 to clear the Turks out of the foothills. Pratt’s image notes it as near ANZAC Cove where the main landing occurred on April 25, 1915, the foundation event used to mark Australian and New Zealand nationalism and celebrated on that date on ANZAC Day. This Gallipoli Campaign cost the Allies 187,959 killed and wounded and the Turks 161,828. Gallipoli proved to be the Turks’ greatest war victory, for which a 40 year old Winston Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty and in control of his colonial forces, carried a culpability and guilt into the Second World War. The wounded were tended in the erected hospitals on the Greek island, Lemnos from which Pratt had documented their departure. Of his photographs of Mules at No. 2 Post near Bauchop’s Hill; are these a trace to the mythic donkey Simpson used to cart wounded soldier’s to safety?

Pratt’s role, for which he remains invisible, in documenting such on the ground events, has become redundant. Contemporary I-phone images of bombings and mutilation spin war atrocities around the world, in constant surveillance machine churn to be processed by an audience framed through the headless crowd mentality Gustave le Bon identifies in The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895).

Pratt’s invisible trajectory through surveillance and photography that skirts contemporary issues of truth, nationalism and history is traceable through his technical knowledge and achievements.

Charles Pratt was a quiet retiring almost shy type of person, as related by those who know him. One of those who stayed at the back of a group rather than hold court despite his achievements. (Reilly, p.1 2016)

4.

Re-Looking

… [to] make sense of reality, to re-construct and present it in a way that seduces the observer into a re-examination into seeing the relevance of those things that had previously been hidden or unobserved? (Yates 2007: 164)

Crashed German Rumbler

Pratt’s aerial images have a temporal and durational framework, specifically the duration of the investigation of the site and place, and the coding of this into material and mechanical media. By revisiting these historic images, we may be able to refocus attention on the moment of time as well as the exploration of history through the lens of contemporary understandings. As we look out from afar, we see grid formats as dark and light spaces appear and disappear. Having glimpses of open fields, the ocean, or the roadside, we experience a brief moment of grounding, only to turn around again when we contemplate the horizon from a distance.

Despite being captured from a distance, this view appears familiar and intimate, as if we know the Geelong townships and these roads. I wonder what difference a contemporary drone capture or Google images will make compared to this perspective. In these works, I am intrigued by the chemical-based photographic technologies at play rather than the distancing, fixed gaze, or decisive moment that traditional considerations of documentary or monocular photo vision suggest. My thoughts turn to the incidental-happens that mark the emulsions of the prints add to the narrative. Each image contains a physical, tactile mediation embedded in their surfaces that entices me to look again, resulting in a sense of extension to the story. I do not direct my gaze by preconceived contexts of a city, landscape or event when re-looking and considering the tactile imprints in the final images. I am drawn in by the simulated relationship between the terrain and past memories of melancholy. As a maker, I am interested in this way of looking, knowing, of being, that is revealed through the making; Pratt’s images promote this act of material and intra-activeness as an agency of encounter. My attitude and observations are informed by the photographic performance that Pratt’s images promote.

This re-look is not intended to (re)record or (re)document a particular moment, but rather to respond to pictures of landscape, happenings and process. It explores representations of landscapes and happenings and their surveillance, emphasizing and visualizing the physical, mental, and spatial aspects of emotional response. This is where, for me, notions of surveillance and aesthetics extend. It is no secret that surveillance recordings are now an integral part of our daily media experience. Terrain and satellite images of war atrocities from the Ukraine are broadcast on social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram. These images inform our news streams and cancel culture. Images and trends are captured by amateurs to inform, entertain, and educate. In addition to immediate viewership and collaboration, viewers can instantly respond, discuss, and express themselves. New media and notions of landscape images have changed in the way we interact with them, and one part of this shift has been the reliance on perceptions of surveillance. Pratt’s aerial and landscape images contribute to the exploration of this by way of contemporary revisioning and understandings.

3 Flying boats in Corio Bay 1927

References:

Abram, D 1997, The spell of the sensuous: perception and language in a more-than-human world, New York: Vintage Books.

Preston, Lesley “Second Rate? Reflections on South Tech and Secondary Technical Education 1960-90”, Doctoral thesis, Faculty of Education, The University of Melbourne 2005.

Reilly, Kevin M. 2016 Charles Pratt of Belmont Common: a life in the air, Dingley Village.

Sontag, S. (1977). On photography. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Yates, A 2007, ‘Looking and listening’, Pichler, B and Slanar, C (eds) 2007, James Benning. Österreichisches Filmmuseum.

Dirk de Bruyn (1,3)

Wendy Beatty (2,4)