Free trade, food systems and dietary change in the Pacific

October 9, 2017

Studded across the vast Pacific Ocean are twenty-two small island nations and territories, home to a diversity of population sizes, geographies and cultures. Among these palm-swept islands, one of the clearest examples of food systems and dietary change in modern history has played out.

This change has been driven, at least in part, by the processes of free-trade (or ‘trade liberalisation’). That is, the removal of barriers to cross border trade and investment.

Alfred Deakin Post-Doctoral Fellow, Dr Phil Baker offers a brief introduction to this topic.

Diet-related noncommunicable diseases in the Pacific

“The burden and threat of non-communicable diseases constitutes one of the major challenges for development in the twenty-first century.” So stated the United Nations General Assembly in 2012. And nowhere more than in the Pacific Island countries (PICs) is this true.

PICs account for eight of the world’s ten most obese nations, and seven of the top-ten with the highest rates of diabetes. Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes account for 75% of deaths in the region and cause considerable long-term illness and disability.

This situation is putting unsustainable financial pressure on health systems and entire economies. The cost of NCDs to eleven PICs was estimated to be approximately 13.2% of gross domestic product in 2015. Pacific leaders have collectively declared NCDs to be a ‘health and development crisis’ in the region.

The linkages between free trade and diet-related NCDs

Free trade is about removing barriers to the flow of goods, services and investments across country borders. This can happen when countries sign-up to free trade agreements (e.g. by becoming a member of the World Trade Organization, or by signing up to a free trade agreement with one or more other countries).

In doing so, countries are obligated to reduce tariffs (i.e. taxes on imports) and restrictions on investments by foreign companies. This can have significant impacts on food systems. For example, it can mean increased food imports, and increased investments and marketing activities by foreign companies throughout the food chain (e.g. in food manufacturing, fast food or grocery retailing).

Importantly, trade agreements also contain rules about how governments can regulate their markets. This can limit the scope of policies and regulations governments would otherwise use to protect and promote good nutrition e.g. restrictions on the imports of unhealthy foods, advertising restrictions on energy-dense foods, product labelling regulations and so on.

Together, these process can significantly alter the availability, nutritional quality, prices and desirability of local foods.

Free trade, food systems and dietary change in the Pacific

The processes described above, in particular increased food imports, have had significant impacts on food systems and diets throughout the Pacific. Previously known as nations with ‘subsistence abundance’ prior to European contact, many Pacific nations can now be called ‘dietary dependent’. That is, they have become increasingly reliant upon food imports from other countries.

In a process known as import substitution, traditional diets of root crops, fish and local fruits and vegetables have, since the 1960s, been increasingly displaced by imported, often highly processed foods such as white rice, flour, canned foods, instant noodles, low grade fatty meats and sugary drinks. The proportion of food expenditure on imported and non-traditional foods has approximated or exceeded 50% of total food expenditure in Kiribati, Samoa and Tonga.

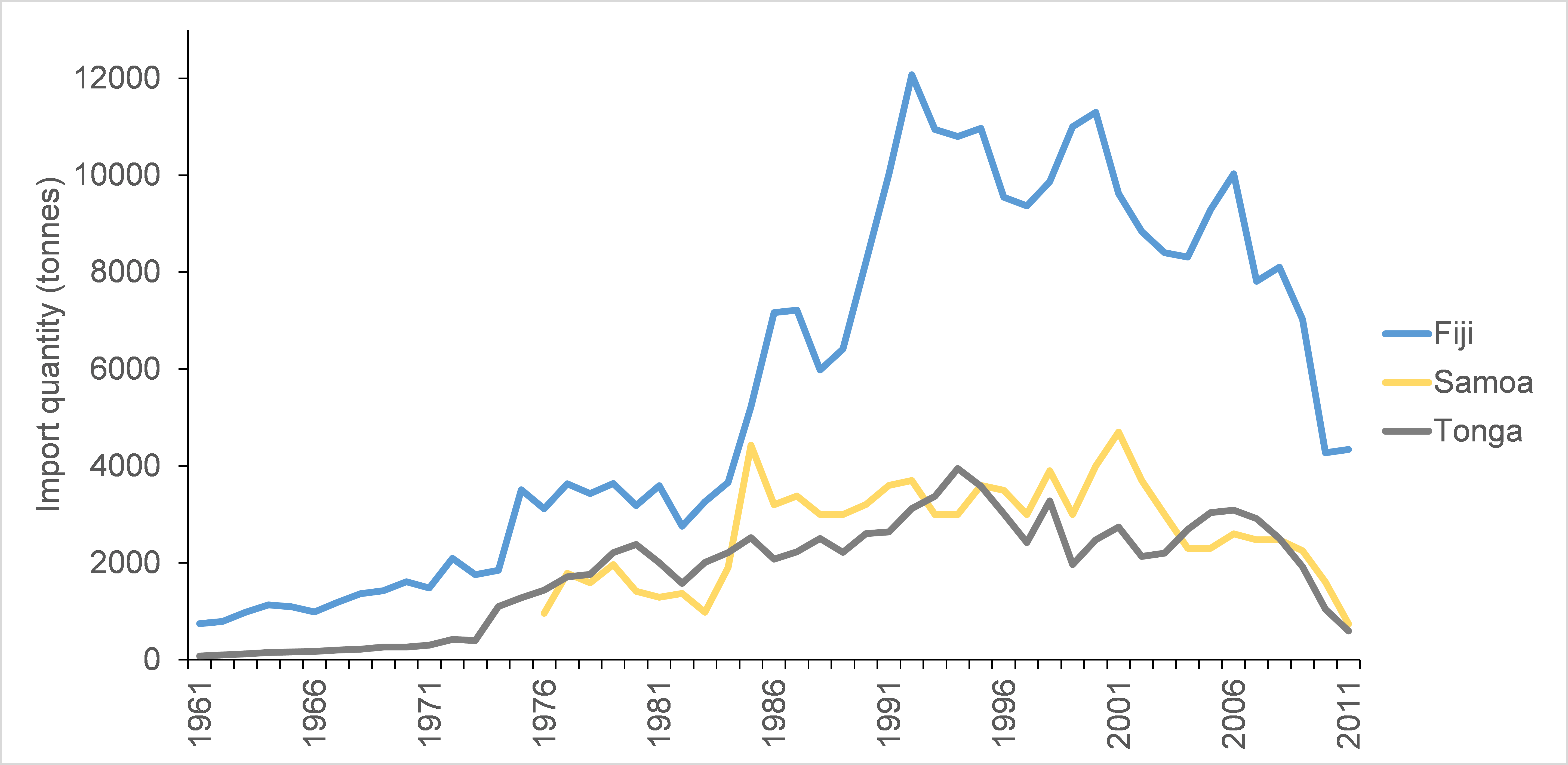

Some countries have also been labelled ‘flap-food nations’. Mutton flaps, low-grade meat product containing up to 40% fat, has been exported to the Pacific by the New Zealand and Australian sheep industries since the 1970s. Although imports have recently declined, they remain a staple food for many Pacific peoples (see figure).

In Tonga, for example, mutton was the second largest household expenditure item behind chicken off-cuts (also mostly imported) in 2009. Large volumes of turkey tails, similarly unhealthy and imported predominately by countries with historical ties to the United States, have made their way into Pacific diets. A Tongan study found that low-fat traditional sources of protein, such as fish, were between 15% and 50% more expensive than these fatty imported meats.

Imports of sheep meat by Samoa, Tonga and Fiji, 1971-2011

(Source: FAOSTAT. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/)

Free trade is also linked to issues of food security and agriculture. Increasing dependency on imported foods can displace domestic production of traditional crops. And when there is an over-emphasis on growing so-called ‘cash-crops’ for export, rather than foods for domestic consumption, populations can become vulnerable to global food and fuel prices.

Towards healthy trade in the Pacific

The above observations call into question the benefits of free trade against the costs in terms of food systems change and human health in the Pacific.

Fortunately, several PICs are world leaders in the adoption of policies to combat unhealthy diets. For example, Fiji, Nauru, Tonga, Samoa and Kirabati have adopted taxes on sugary drinks (some have also adopted import duties on them).

Tonga has further introduced a 15% import duty on turkey tails and lamb flaps, while Fiji has imposed a 35% import duty on palm oil. Tonga has reduced import duties on fresh, tinned or frozen fish, and Fiji has done so on imported fruits, vegetables and legumes.

These developments bode well for healthy diets in the Pacific. The challenge now is to accelerate the adoption of similar measures throughout the region.

Dr Phil Baker, Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Institute for Physical Activity and Nutrition (IPAN), Deakin University