Belle Gibson, the health and fashion industry, and the willing suspension of disbelief

When I stay in a hotel, there is a tacit agreement that I (the guest) will pretend to not know that someone slept in the bed and used the room before me, and in return they (the hotel) will do everything they can to remove any evidence that somebody has been in the room prior to my arrival.

When I stay in a hotel, there is a tacit agreement that I (the guest) will pretend to not know that someone slept in the bed and used the room before me, and in return they (the hotel) will do everything they can to remove any evidence that somebody has been in the room prior to my arrival.

A stay in a hotel is, in its way, something akin to the willing suspension of disbelief.

If we both comply with that little bit of fantasy, it tends to work. But, ultimately, we are all playing a role – actors in a piece of

theatre that allows us to dismiss the complex reality of the world.

Life is a little bit like that. We go through life playing particular roles that suit the circumstances, while processing information that seems to help us to understand our little piece of existence, and ignoring information (whether consciously or unconsciously) that doesn’t work for us at that point in time.

So, it’s no wonder that for people who have been struck down with an acute illness (or knew someone who had), such as cancer, it was so easy to believe the story of Belle Gibson.

Gibson weaved a wonderful narrative that appealed to her target market – the colour magazines, the magazine TV shows, and light radio – because she could have been one of them.

She was young. She told us her life had been difficult. She had suffered. Just like we had.

Her story seemed plausible. She used medical sounding words that were familiar, but she didn’t overwhelm us with jargon or complexity.

Her story was reality television; we wanted a happy ending and Belle gave us one, with the assistance of much of the media playing its designated role – keeping “real” reality and messy complexity at bay. She was, we were told, “authentic”.

All in a four-minute interview, between ads for Veggetti™ and fun ship cruises.

She told us a story, and the media helped us to weave ourselves into its narrative.

And, as any marketer will tell you, narrative is so much more powerful than facts and information. Particularly when compared to the abstract, impenetrable world of science.

Science is complex, remote, and clinical. It requires effort to process. It has its own internal language that often requires a university degree to completely comprehend.

Science talks in probabilities, not in definitive outcomes.

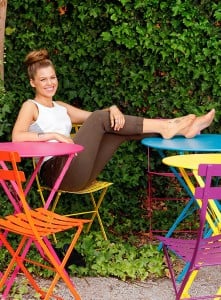

But, the lovely Belle told us stories, and the media helped to explain those stories by matching them with beautiful pictures of the brave Belle standing next to fruit and vegetables, and sitting, happily in her garden.

Belle’s story felt right to many people who have suffered through the horror of being told you have an illness that could take your life. The hope she provided felt tangible, and the ability

to fix the problem using methods that are understandable – changing your diet, buying an app – seemed so much more palatable than being injected with, what is ostensibly, a poison designed to wipe out the matter that keeps you alive; your blood cells.

Chemotherapy is scary.

Eating fresh fruit and vegetables is not.

Belle fulfilled her main role as a member of the inspiration industry. She played her part in the inspirational theatre that supports the health and wellness sector. She did what the best products do.

She gave us hope.

In Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel, Oryx and Crake, one of her characters asks whether we are “both saved, and doomed, by hope”. It is hope that drives marketing – hope for a better future for ourselves, for our families, for the planet.

Belle was one of those pithy quotes that we repost on Facebook, to show that we are strong, or brave, or some other third thing.

She didn’t talk about cancer in probabilities. She provided a colourful, attractive counterpoint to the complexity and contingencies of science.

Yes, we were duped by Belle. And yes, her lies may have resulted in some people not seeking treatment.

But we were also accessories who were not interested, or perhaps too frightened to engage, in the facts.

In return for being inspired, we entered into a tacit agreement not to think too much about the reality of what Belle was telling us.

It wouldn’t have taken much for someone, anyone to find her story just a little implausible. As the Sydney Morning Herald reported once her story started to fall apart, “I asked her when she got her diagnosis, she said she didn’t know,” “I asked her who gave her the diagnosis, she said Dr Phil. I asked her where she saw Dr Phil, she said he came and picked [her] up from [her] house.”

Her diagnoses for terminal brain cancer (acquired from a vaccine), three heart surgeries, three minutes of being clinically dead, two further brain cancers, and cancers of the blood, spleen, uterus and liver was from a guy known as Dr Phil… who picked her up from her house?

There were plenty of alarm bells, but no one stopped to listen, because we were too busy engaging in the inspiration.

But, I can also understand why nobody felt comfortable asking her to prove it. In a way, it wasn’t really up to Belle to prove it. It was up to those reporting on it to make sure she was telling the truth.

But that would be journalism, not inspirational theatre.

Which brings me to my conclusion.

I think we need to talk about cancer. In terms of its cure rates, advances in knowledge, and how people cope with their cancer, but also in terms of its messiness, unknowningness, and complexity. To recognise that it can be positive, but it also can be horrible.

And we need to talk about probabilities. To remind ourselves that science, and medicine is methodical, complex, and always provisional, but constantly looking to do better.

In 1759, François-Marie Arouet, (AKA Voltaire) wrote a satirical novella about a young, overly optimistic man, Candide, that parodied the adventure, inspiration, and romance of, what could be contemporarily interpreted as, the optimism industry. By the end of the novella, Candide realises that the world can be a messy, complicated place, and retires tend his garden – one interpretation of which is that progress leads to the improvement of the world.

Belle Gibson has given us just a snippet of an opportunity for us to stop and tend our garden.